- This topic has 0 replies, 1 voice, and was last updated 3 years, 6 months ago by

Alec Kotler.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

October 18, 2021 at 12:17 am #8421

Alec Kotler

Participant

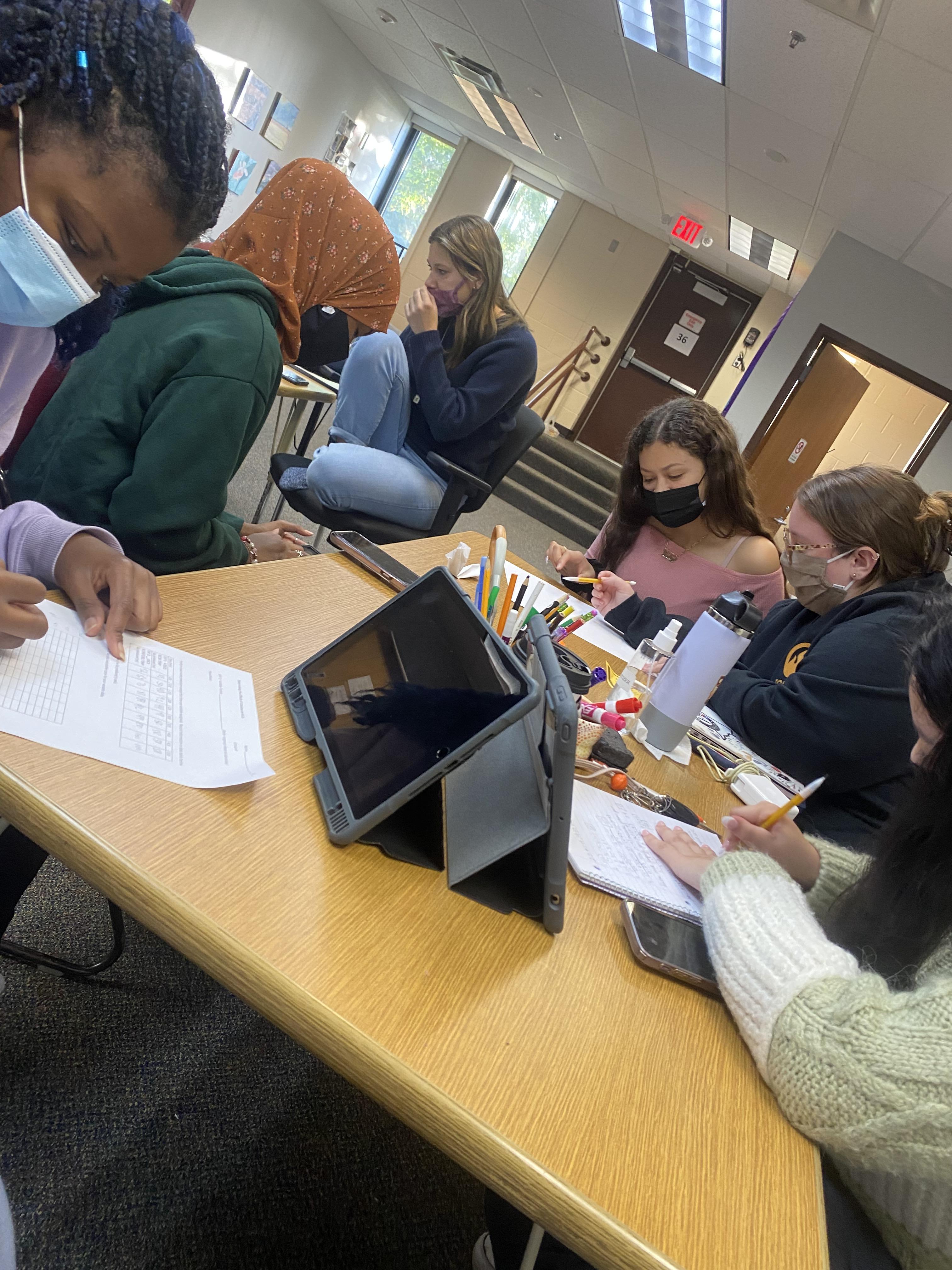

The students I am observing and working with would fall into the psychosocial stage of identity versus role confusion according to Erikson. These tenth graders are around the ages of 15-17 (many being too young to drive a car!). They are still unsure of who they are or what their purpose in society is or will be. As these students interact, collaborate, and complete various assignments in biology it is easy to observe and understand particular interest levels surrounding the subject as a whole for specific individuals. As an observer trying to identify how far along these students are on Erikson’s psychosocial development scale, I am able to formulate some hypothesis, but at the same time there are some glaring confounding factors. These students spend all day in school going to a variety of classes such as language, math, English, study hall, and sciences. I only see these students in one of their classes. I do not get the full picture. Some are easier to analyze than others, such as those who are very expressive physically – wearing their identity on their body. Many of the athletes, for example, routinely wear their team’s jerseys and show up to class with athletic “swag” -as teenagers like to call it these days. Some of these students identify as athletes and are seemingly determined to pursue that label post high school. That, however, is just from observing appearance. Observing their interactions are limited to their interest in one subject -biology. Students who are more engaged with specific tasks than others and express creativity in certain assignments seem more comfortable in their role as hard working biology students and seem to embrace the understanding that they need to learn the basics to pursue unknown findings later on. Those in the class, and there are quite a few of these types of students, who are on their phones, snapchatting, texting, listening to music, or on their iPads playing a video game are clearly disinterested and not attentive to Mr. Johnson. When these same students are assigned an experiment, they mostly can perform the task required, but it is in how they complete the task that suggests discomfort with the identity of a young, budding scientist and more role confusion than the other students. Their nonchalant attitude I don’t just observe through their appearance and actions, but also through what they say. Some ask “why are we doing this?”, while others proclaim “I don’t like science”, or “I don’t care let’s just finish.” It is a type of attitude and lack of determination that I sense as a certain wandering. Perhaps, these teenagers have already decided that their role in society will have nothing to do with science and that is how they identify. The more likely conclusion is these students are in a mindset of indifference. Why do they need to be in class? Why are we doing what we are doing? They are not committed to fully engaging in the exploration. This is a mindset that inhibits expression and choice and instead leads towards confusion. When these students struggle to express themselves and engage in certain things, they have trouble pairing up with peers as well. It is only 10th grade, so obviously there is plenty of time to work through this crisis, but it may require extra guidance from a more knowledgeable other.

Mr. Johnson does a wonderful job setting up a classroom environment where his students have opportunities to not only express themselves but to explore. These are characteristics that imply Mr. Johnson is facilitating identity development. In most classes, lecturing is some component in one way or another. It is very difficult to get away from lecturing completely. Most of Mr. Johnson’s class, however, is structured through student run experiments and group discussion of results. The few times Mr. Johnson does lecture, he conducts it in a very unique fashion. Instead of a standard method of teaching from the textbook or teaching to a test, his main focus is promoting student engagement. He grabs attention for new concepts through first performing really motivating and diverse experimental demonstrations in front of the class. This allows the students opportunities to make observations and discuss what they found interesting and what they might like to try next. Several times, I have noticed students responding to a peer’s observation and in doing so making a connection to something they saw or learned earlier in class, or some other avenue they might like to try. These opportunities, allowing for outward expression and choice, are critical for promoting identity development. This same opportunity is extended in the majority of the class when the students are able to do certain experiments themselves. This part of class facilitates development further because it brings a chance to insert independence into the picture where the students can determine what their role is not only in the experiment, but as a scientist in general. Even for those who already think their lives won’t revolve around research or science, they still benefit from this activity as they can express themselves and practice collaboration.

Though Deborah might disagree, I probably need to classify myself as in identity foreclosure (with respect to some things) and identity achievement (with respect to others) within Marcia’s extension of Erikson’s theory. The most specific I can be in describing this reality is to tentatively proclaim that much of my athletic and academic interests developed in such a way that Marcia would describe as identity foreclosure. As a 4 year old, my grandpa (an ex pitcher who tried out for the Cubs) threw me a baseball and demanded I hold on to it. Later he rolled me a ball, and I threw it back per his request. Later, he put a bat in my hand and I took a swing. Then, my dad signed me up for little league. With little practice, I was already the best player on the field. I was supposed to stay on the field. You can’t stop doing something if you are the best at it. At a young age, I had a sense that “being good” might not be a good enough reason to do something, and have continued to believe that till now. Of course, I always had the freedom to stop, and I never wanted to, but it’s hard to know given those beginnings how free the choice really was. My academic interests were similar. My parents went to Amherst College and Emory University. I was supposed to choose a prestigious college. I chose Carleton. My grandpa is one of the most well -known nephrologists in America and he reminds me of that at every Thanksgiving I can recall. I also studied hard to get good grades because I was supposed to. Of course, in high school I had a certain drive to do well but that is not me resolving a crisis. That is the expected result of constant years prior where my parents, mother specifically, would preach good study habits and give me constant external motivation. I do believe that this external motivation became internal. Yet nothing was really actively decided by myself. You spray perfume in a corner of the room, eventually the scent makes its way to the other corner in a room. Studying hard is the only way I know how to approach school. There was never another way for me to do school. When I was a kid and a teacher asked me what I want to do when I grow up (I don’t understand why they ask kids these questions at school at such a young age. Seems like a thing to do to kill time.) I would always respond by saying “I guess a doctor,” that was after they would laugh at my saying “a professional baseball player”. The truth is, in didn’t really connect to any particular classes in school. Eventually, I did walk into a certain science class one year that really grabbed my attention and, luckily, by senior year of high school I fell in love of the sciences, but I believe that to be random, not a resolution. There simply had not been enough exploration. There was, however, a lot of expectation.

In other areas though I would have to say I am in identity achievement. Many examples come to mind but I want to focus on religion and independence. I was terrified going into college. Managing everything on my own was a certain experience I didn’t have growing up. This summer, four years after being initially dropped off at college, I was working in Salt Lake City managing my money, living space, transportation, and every piece of life that “adults” are supposed to be doing. Growing up I was very dependent on others to function. I do feel as though have resolved a certain identity crisis and am really committed to being an independent individual and I am quite competent at it as well. I also feel that I have reached identity achievement when it comes to religion. My father grew up in a Jewish household (more Conservative than Reform) and my mother cherishes the religion from a cultural perspective. I became a Bar-Mitzvah in Israel, my favorite family trip to date. Religion has held little value to me – primarily influenced by my science background and my ambitions to keep life in my own hands and not put it up to faith’s motive. So this has been a bit of an identity battle. A strong proponent in this battle is my father who I respect and love and don’t want to let down. He is very religious and it means a lot to him so I struggle with avoiding the Jewish culture all together, but I believe religion is not important to me. At this point I have resolved this conflict by considering myself as Jewish, but with no intention on that affecting me in any way. I am a Jew to the extent that I support my family, but I am a Jew with no intentions of actively engaging in the religion in any way.

This week of tutoring was different from the previous couple. Instead of spending all of my time with Mr. Johnson’s class observing, I was bouncing around helping specific students and observing another class. Mr. Johnson’s classes were taking a test so it would’ve been useless for me to just observe the students face down in their exams. I spent part of my day in a study hall room where I helped a female student with her calculus and another female from Mr. Johnson’s class with a post-lab assignment. Both of the students were asking very interesting questions and were clearly determined to learn. It took a little bit for me to recall my Calc skills but I was able to and felt helpful and useful – which was very satisfying.

Then I spent the rest of my time in an industrial chemistry class taught by a teacher not named Mr. Johnson where I noticed something surprising and a little upsetting. A couple students were on their phones the entire class as the teacher was lecturing. He didn’t address these students till the end of class but he called them over as well as telling these students to stay behind from everyone else as the bell rung, indicating dismissal. Both students were visibly upset and not receptive to what the teacher was saying to them and, in fact, they were both defensive. This is clearly an issue the teacher needed to handle, but I don’t think Kohlberg would approve of his method. It felt as though he was shaming the students. What is the best way to approach this issue? I didn’t like this teacher’s approach, but also recognize that the students’ behavior needed to be addressed and I’m not sure the teacher had ample time to consider the best method for doing so.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.