- This topic has 1 reply, 2 voices, and was last updated 3 years, 6 months ago by

Isaac Fried.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

October 29, 2021 at 5:48 pm #8529

Lauren Bundy

Participant

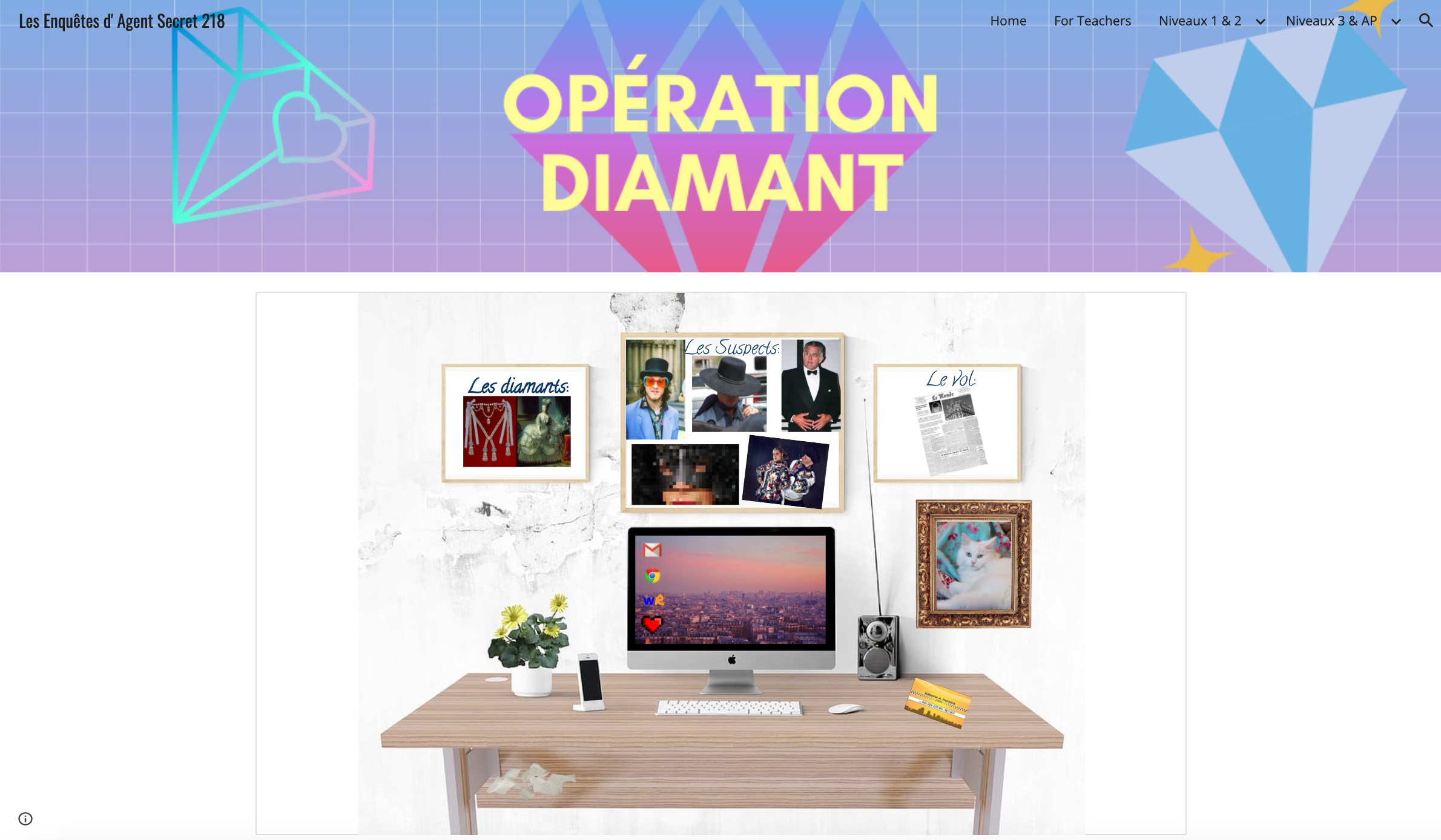

On Monday, I got the opportunity to lead both French 4/5 and French 3 in their activity for the day: an online escape room! Denise found a website created by another French teacher, containing seven different mysteries to solve. I agreed to guide her students through one of the missions as the lesson for the day, which means that I got the chance to teach a bit (although it was mostly a self-guided activity) and she got the chance to catch up on some grading—a win-win situation, I’d say. I selected Opération Diamant because it looked like it could fit within a class period (some of the other missions were supposed to take 2-3 hours) and because it was targeted for more advanced French students and I thought the students deserved a bit of a challenge. The goal was to figure out which suspect stole a woman’s diamond necklace. After spending part of my Friday evening solving the mystery myself, I felt ready to introduce the activity to the students and offer hints when necessary.

Admittedly, much of my analysis of the reinforcers used in the classroom comes not from my own work with the students, but from their interactions with the online activity. These observations still seem pretty apt to me, considering that Gredler wrote, “Skinner (1989b) considered the computer as the ideal teaching machine” because of the potential they offer for reinforcement (p. 125). Indeed, I watched as groups of students got excited when they finally found the right password to make a call on the phone or when they found the safe hidden in the dressing room. Successfully solving a riddle would reveal a new clue, and each clue served as reinforcement, causing the students to continue the activity until they gathered enough information to determine which of the suspects stole the necklace. In most cases, the reinforcements not only encouraged the students to solve the mystery, but also to practice their French by working with the riddles and the resources provided to solve them. This intended consequence was occasionally undermined by students who merely guessed who the thief was until they got the right answer. Although I did see a handful of students doing this, resulting in the immediate gratification of solving the mystery but not much French practice, I was pleasantly surprised by the number of students who were genuinely invested in solving the mystery by interacting with all of the resources provided through the website. When the bell rang at the end of class, I heard a few students expressing disappointment that they hadn’t finished yet.

I really want to consider myself a cognitivist; I’d like to think that students do in fact have free will and shape their own learning. That being said, cognitivism is harder to observe in the classroom because I can’t see inside students’ minds. However, I did notice a particular instance of students retrieving knowledge on Friday that they had added to their schemata on Monday that I think can be explained through cognitivism. The escape room’s riddles were often based on information about Marie Antoinette; in one instance, the students needed to complete the famous, misattributed quote, “Qu’ils mangent de la brioche” (“Let them eat cake”) based on information they could find on the escape room website. On Friday, students were discussing things they had dressed up as for Halloween in the past, and one student mentioned that she once dressed up as Marie Antoinette. In response, Denise mentioned the “Let them eat cake” quote in English, but she wasn’t sure of the French equivalent, wondering if “cake” was translated literally from “gâteau.” Several students then responded, accessing information they had learned from the activity on Monday to correct her—it’s actually “brioche,” not “gâteau.” Clearly, Denise didn’t explicitly reward or punish them on Monday to promote retention of this knowledge (seeing as she didn’t know it herself), but students integrated into their schemata nonetheless as the result of an experience on Monday.

I’d also like to try to assess the applicability of Bandura’s social-cognitive theory as it relates to Denise as a role model shaping student behavior. Although I can’t be sure as an outside observer, I do think that students have a fairly good relationship with Denise; at the very least, she seems genuinely invested in the lives of her students. At the beginning of class on Friday, two students came into class complaining to each other that another student (not one in the class) acted entitled and treated them poorly. Denise demonstrated interest in the students’ concerns and talked with them about ways they could interact with this student in the future. At other points throughout the term, I’ve noticed her talking with students about the sports they play or the jobs they work. Students seem comfortable joking in her presence or talking to her about their concerns outside of class. It’s actually quite surprising to me, because I can’t recall having that kind of relationship with any of my high school teachers.

Now I’m going to assume that the rapport between Denise and her students shapes their internal cognitive processes and causes them to see her as a model of sorts, causing them to emulate her behaviors. As I’ve already written in numerous blogs, I’m generally disappointed by the lack of French spoken in class, but I believe this is modeled by Denise, who consistently translates words or has conversations entirely in English. If the students do in fact consider her a model, they’ll see that behavior as acceptable behavior in class and replicate it—which they do. Of course, this could also be explained through a behaviorist model: students aren’t punished for speaking in English, so they continue to do so. I think this eliminates the human aspect of education though, especially considering that many of my observations in Denise’s class have revolved around interpersonal relationships—the “social” aspect of Bandura’s social-cognitive theory.

My final commentary for this week brings me back to the escape room activity. I mentioned that several groups became very invested in the mystery, especially as they advanced through the various tasks. French 4/5 was a bit quieter, often working in near-silence, but French 3 was especially animated. However, one group of French 3 students in the back of the room decided early on that, while the other groups were smart, they were “idiots,” as one group member put it. He said it jokingly enough, but it made me sad nonetheless. Maybe this can be explained with a behaviorist approach—the students didn’t solve any riddles early on, thus depriving them of the positive reinforcement other groups received and causing them to give up on the activity—but the way that all four students accepted near the outset that they weren’t smart enough to complete the activity could also be viewed through the lens of self-efficacy. Somehow these students internalized their inability to complete the task before they really started, thus setting low expectations for themselves and failing to complete the activity. While this week offered a pretty rewarding experience for me, it also revealed some of the challenges teachers face in inspiring student confidence.

-

October 29, 2021 at 7:57 pm #8532

Isaac Fried

ParticipantAh the escape room activity sounds so fun! I actually tested out a high school geometry teacher’s homemade escape room challenge (he is the friend of my partner, a Carleton grad, and coincidentally my little sister’s teacher!) I really enjoyed the embedded reinforcement of literally unlocking the next clue, finding the correct room, and getting the right code to solve the challenge! It feels good to be rewarded, but I do see how struggling initially (and without positive reinforcement) can be discouraging and lead to failure.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.